I. Looking at Books

Books, for some of us, are like friends—indeed,

it might not even be entirely too extravagant to suggest

that perhaps,

for some of us, they figure among our closest of friends.

If at first it is striking to notice the presence of books

in

so many of Frank Mason’s portraits, and further

thought, diminishing the surprise, confirms the proximity

of books in

our lives, then lingering with his paintings in a contemplative

spirit may provoke, in still further thought, a wonderful

revelation of this intimacy. In “Artist’s

Father Reading” (1941),

the gaze of the beholder is gently drawn into the pleasure

of an intimacy so singular that it eludes the grasp of

words.

Books, for some of us, are like friends—indeed,

it might not even be entirely too extravagant to suggest

that perhaps,

for some of us, they figure among our closest of friends.

If at first it is striking to notice the presence of books

in

so many of Frank Mason’s portraits, and further

thought, diminishing the surprise, confirms the proximity

of books in

our lives, then lingering with his paintings in a contemplative

spirit may provoke, in still further thought, a wonderful

revelation of this intimacy. In “Artist’s

Father Reading” (1941),

the gaze of the beholder is gently drawn into the pleasure

of an intimacy so singular that it eludes the grasp of

words.

We are surrounded by books; yet their presence is often

reticent, accommodating other concerns. In Mason’s paintings, this

reticence is respected without forfeiting the lucidity of a

relation that it would perhaps not be inappropriate to describe

as distinctively “ethical” in its character. This

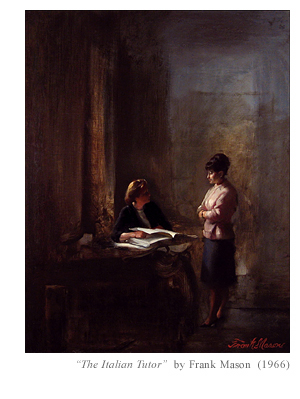

impression is especially compelling in “Anne and the

Italian Tutor” (1966), where it is rendered with the

most tender of sentiments. It is also to be noticed in “Anne

Reading Ouspensky” (1967) and “Young Emersonian” (1989),

and, with more reserve, in the portrait of Sir Winston

Churchill (1952).

Of course, two paintings in this exhibition make the

book its principal thematic, celebrating the book in

allegorically

suggestive

representations: “The Book of Ages” (1976) and

the more recent still life, “Book and Candle” (1995),

with its luminous atmosphere of baroque melancholy, reminiscent

of the works of the religiously inspired French painter, Georges

de la Tour (1593-1652). And in one of the paintings in this

exhibition, “Bach Fugue No. 5” (1949), it

is not a book, but rather a musical composition, a page

of

musical

notations, beautifully inscribed, that the painter celebrates,

offering a work of exceptional lyricism, its melodic

flow of lines, contours, and forms itself a fugue, evoking

for

the

activity of vision a lyrical replication of the musical

experience.

II. Portraits

In Frank Mason’s portraits, something important about

the character of the individual always comes to appearance.

The artist’s gaze, behind, or before, the production

of these portraits, is moved by a warmth of feeling, a benevolence,

a generosity of spirit, receptive and hospitable to the enigma

of that appearance. What is enigmatic most of all is the way

in which he simultaneously touches on something enduring whilst

releasing the stayed moment to the grace of its temporality.

Perhaps, for obvious reasons, this is most noticeable in his

family portraits: Anne Reading Ouspensky”, “Artist’s

Father Reading”, and “Artist’s Mother at

Tea” (1945); but the portraits of Winston Churchill (1952)

and Percy MacKaye (1951) are no less exemplary in this regard,

for they too, by way of their subject, present to the gaze

of the beholder the gaze of the painter, the sympathy in his

vision embodied in the gestures that have determined the touching

of the brush on the canvas. In the portrait of the artist’s

mother, the painter’s love is embodied in the movement

of brush strokes with a lyrical quality reminiscent not only

of the serene restraint of Vermeer, but also of the freely

expressive brushwork of Frans Hals. And in Mason’s “Othello” (1964),

these brush strokes have been released to a bold, expressive

intensity that evokes not only the dramatic presence of the

subject but also the drama of the artist’s vision itself

as it recorded its felt sense of the encounter in the tracework

of paint. The powerful energy manifest in the brush strokes

that evoke Othello’s robe reveal more immediately than

any words could the wild, impulsive nature of Shakespeare’s

tragic character.

III. Semblance

In Frank Mason’s works, as in the paintings of all great

painters, the mystery and magic of painting—that wondrous

emergence of semblance—will be missed if one overlooks

the touches that are seemingly without significance: for example,

the glistening silver on the domes in “Maria della Salute,

Venice” (1984), the touch of white beneath the left hand

and the equally luminous orange placed to the right in the

portrait of Churchill, the light from the window that spreads

its pale hues on the floor in “Art Students” (1983),

the brilliant triangle of white at the top of the book in “Anne

and the Italian Tutor”, and the impasto effect on Othello’s

forehead. To call attention to only a few of the innumerable

little touches that make all the difference in the world—quite

literally, in fact, making the difference between the compelling

emergence of a world and the failure of the work to reveal

any compelling world.

IV. Background/Foreground

Mason’s paintings—be they portraits, still lifes,

or landscapes—show a master’s love of the background:

not only, like Rembrandt, a deep insight into the significance

of the background as a dynamically recessive spaciousness that

grants visibility, grants presence, to that which is presented

in the foreground, but, possibly more fundamentally, and again

like Rembrandt, the fearlessness which enables him to surrender

the demand for visibility, yielding to the drama between emergent

forms and invisibilities taking place in the background. Like

the backgrounds in the Dutch master, the backgrounds in his

portraits, however dark, have a wonderfully expressive vibrancy.

In “Anne and the Italian Tutor”, for example, the

two women are situated—or rather encompassed—in

what appears to be a very large room; the features of this

room are only hinted at through the encompassing darkness.

The effect of this composition, giving the background such

a powerfully intense presence, giving it the quiet force of

the possible, is to bestow upon the encounter, the conversation,

a dramatic, even enigmatic quality, provoking the beholder

to contemplate many different interpretations and imagine many

different narratives, to inform what is there to be seen. In

other words, the looming background, though in purely objective

terms greater than the women, actually concentrates our attention

on them, instead of diminishing their presence. But it also

at the same time renders their relationship intensely enigmatic,

creating a dramatic moment that suggests countless possible

narratives. What is the question that causes Anne to cease

reading and call upon the tutor? Or what has the tutor said

to Anne that causes her to look away from the book, using her

hand to keep her page? What is being said? The background,

in this painting, is sheer alembication—and the most

absolute of questions.

Most of all in Mason’s portraits, but also in some of

his other works, the sublime presence of the abyssal, the presence

of absence, looms: it is as if, whilst celebrating their subject,

these paintings understood the haunting fate of mortality,

the transience of all things sensible. If the darkly looming

backgrounds in the portraits seem to embrace the figure in

a womblike enclosure, warm and benevolent, they also remind

us of the impenetrable night that is death and the tomb that

is waiting. “Book and Candle” is only the most

explicit evocation of this eternal story of transience; but

even the portraits are set into deep, dark, yet intensely dynamic

backgrounds—backgrounds that are warm and hospitable,

whilst also conveying at the same time a profoundly religious

sense of the infinite and eternal, a space-time dimensionality

which transcends worldly existence.

Even the gentle landscapes often yield the majority

of the canvas to the sky, iconographic abode of the

divine

and the

angelic, giving it a strong, living presence, showing

its dominion in the glory of its spaciousness.

V. The Lighting

Mason’s paintings remind us to attend not only to the

light, but to the lighting—to the giving of light,

the advent of light, the appearing of light. In his paintings,

the lighting itself, often a slanting shaft of light coming

from the upper right region of the scene and giving a sometimes

startling incandescence to whatever it touches, becomes

a significant

subject, transforming its condition as mere object to assume

countless roles in the very constitution of the image.

Not the least of these roles is the representation of substantiality,

as if the lighting that the painter lets fall upon things

had

the power to awaken their slumber, to draw them back into

the material world and redeem their insubstantiality; and

yet,

this same lighting also marks the things it touches with

an irrevocable transience, an incandescent ephemerality.

The lighting

is an inscription that signifies the presence of spirit.

VI. Prismatic Reflections

There are some thought-provoking material similarities

between paintings and books. Books are pages of

flat white surfaces

marked with legible print; paintings are canvases,

flat white surfaces, marked by legible paint. Legible

because

visible.

If the printing on the page reflects the shadows

cast by thought, the paint on the canvas reflects

the hand’s

translation of an experience with vision. The printing

represents the traces

of thought, the traces of meaning: it traces the shape

of a thought. The paint on the canvas is the trace of a

gesture:

it is what remains of that gesture, a residue of its shape,

its movement across the canvas. Both books and paintings

are invitations, calling vision to a reading. They are

archives,

investments of sense: their meaningfulness first appears

only through the gesture of reading. Books and paintings

are alive

only when their sensible sense is awakened by the movements

of a vision that repeats and retraces the shapes and movements

it sees before it.

The meaning that book and painting communicate

is not merely something intelligible; it is also,

simultaneously,

something

sensible. The meaning is an intertwining of the

sensible and the intelligible, the visible and

the invisible,

the legible

and the illegible. The words that figure, that

appear in their visibility on the page would be

nothing

without

the white paper,

its empty illegible background: the legible requires

the illegible. Likewise, the configurations of

paint that appear in their

visibility on the canvas would be nothing without

the invisible.

In order to be true to the visible, true to its

truth, the painter must become a guardian of the

invisible,

that sublime

darkness without which there could be no visibility.

The visible is what, in a gesture of the eyes,

emerges, sometimes suddenly,

sometimes only gradually, from invisibility. But

this invisibility never entirely releases it from

its disposition.

The true art of representational painters requires

that they understand the emergence of an illusion,

a semblance,

from

the application of pigment to the flat surface

of the canvas, and are able to let the taking place

of that

emergence itself

come to appearance.

Setting the eyes in motion, a painting comes to

life. What the painter saw belongs to a past that,

by

virtue of its appeal

to its futures, can never be made completely

present. The pigment on the canvas is no more real,

and

no less real, than the temporalities

of its readings.

Paintings, like books, call for readings.

Each reading produces a distinct interpretation. But all

readings

involve codes of

decipherment, an archive of preceding interpretations,

and a rich fund of worldly experience and knowledge.

In both cases,

the eye must be trained; nevertheless, this training

merely develops the capacity to exercise freedom

in the forming of

an interpretation.

Once upon a time, the word appeared

only in letters produced by the hand. In the works of Frank

Mason,

the art of

painting continues to celebrate the gestures of

the hand and the

birth of meaning emergent from the traces left

by the brush in the

hand. The joyful celebration of the creative gesture

is especially evident in his “Othello” and “Artist’s

Mother at Tea”. These paintings manifestly

refute the Cartesian view of the painter who, in

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s

play “Emilia Galotti” (1770), lamented

the gesture’s

mediation as a tragic loss of meaning: “On

the long path from the eye through the eye to the

pencil, how much,” he

exclaimed, “is lost!” Studying these

paintings, what one sees through the lens of our

very different time

and sensibility is rather the operation of a wisdom

in the hands

that no idealization of the art can seriously refuse

to acknowledge: a wisdom, namely, born in the divine

spirit

of love.

- David Michael Kleinberg-Levin